for english scrol down

Am 4. Juli 1833 besuchen Joseph Nicéphore Niépce und seine Frau auf Einladung ihres Sohnes Isidore eine Vorstellung des Théâtre de la rue au Fêvre in Chalon-sur-Saône. Auf dem Spielplan steht die Oper Robert le Diable von Giacomo Meyerbeer. Das Bühnenbild der Aufführung stammt übrigens vom bekannten Bühnenbildner Pierre-Luc Charles Cicéri, bei dem Jaques Louis Daguerre sein Handwerk gelernt hat.

Am nächsten Tag, dem 5. Juli 1833, segnet der Mann das Zeitliche, dem wir die Photographie verdanken. An diesem Tag gibt es in Frankreich weder eine Rue Niépce noch einen Parque Niépce. Erst sechs Jahre später kommt es 1839 in Paris zur Sensation. Frankreich verkündet die Erfindung der Fotografie und Daguerre wird als ihr Erfinder gefeiert. In dem Moment ist vergessen, dass Niépce es war, der nach jahrelanger Forschung 1827 das erste fotografische Bild erzeugt hat. Und obwohl auch Niépce Verdienste 1839 gewürdigt wurden, stand doch Daguerre im Rampenlicht. Ein Licht, dass so stark blendete, dass sich Victore Fouque 1867 bemüßigt fühlte, sein Buch über Leben und Werk Nièpce mit „Die Wahrheit über die Erfindung der Fotografie“ zu betiteln um gleich im Vorwort zu betonen, dass ein Irrtum, sobald er in der Öffentlichkeit einmal verankert ist, eben als Wahrheit angenommen wird.

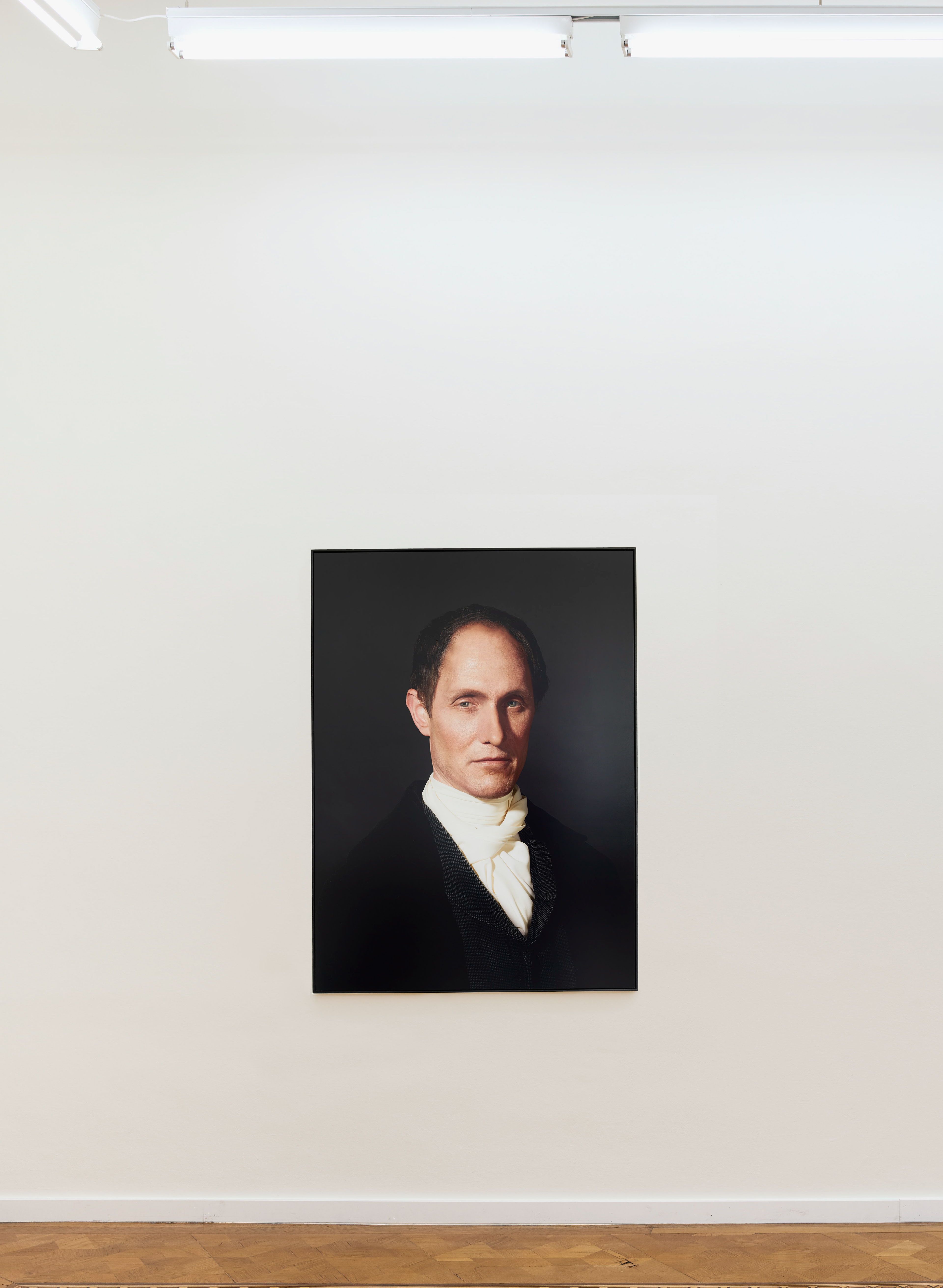

Doch Niépce hat noch ein weiteres Schicksal zu tragen. Es gab keine Fotografie, die ihn zeigt. Sein Tod fand in der vorfotografischen Zeit statt. Von Daguerre gibt es Fotos, ebenso von Hippolyte Bayard und William Henry Fox Talbot, zwei weiteren Erfindern der Fotografie. Aber von Niépce – nichts! Eine Zeichnung, die ihn als jungen Mann zeigt, eine Büste, die sein Sohn Isidore nach seinem Tod angefertigt hat, und ein Portrait post mortem, das der Maler Léonard François Berger 1854 angefertigt hatte.

Wir sind stolz diesem Irrtum der Geschichte nun eine Fotografie entgegenhalten zu können, die Joseph Nicéphore Niépce zeigt. Denn wenn wir als Grundlage unserer Vorstellung der physischen Erscheinung des Erfinders der Fotografie ein Ölgemälde nehmen, dass zwanzig Jahre nach seinem Tod gemalt wurde, dürfen wir mit gleicher Berechtigung dazu eine Fotografie nehmen, die hundertachzig Jahre nach seinem Tod fotografiert wurde. Und wenn das Ölgemälde eine idealisierte Form der Darstellung unter Einbeziehung des Geistes ist, so reflektiert eine Fotografie umso mehr den Geist des Niépce – dieses Erfinders, der 1827 eine beschichtete Metallplatte in einer Kamera acht Stunden lang belichtet und damit ein völlig unscharfes, grobstrukturiertes Bild erzeugt, das den Blick aus seinem Fenster zeigt und der überzeugt ist, damit der Welt eines Tages einen großen Dienst erweisen zu können.

An diesem Tag gibt es in Frankreich weder eine Rue Niépce noch einen Parque Niépce.

On July 4, 1833, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and his wife attend a performance at the Théâtre de la rue au Fêvre in Chalon-sur-Saône at the invitation of their son Isidore. The program includes the opera Robert le Diable by Giacomo Meyerbeer. Incidentally, the stage design for the performance is by the well-known set designer Pierre-Luc Charles Cicéri, under whom Jaques Louis Daguerre learned his trade.

The next day, July 5, 1833, the man to whom we owe photography passed away. On this day, there is neither a Rue Niépce nor a Parque Niépce in France. It was not until six years later that a sensation occurred in Paris in 1839. France announces the invention of photography and Daguerre is celebrated as its inventor. At that moment, it is forgotten that it was Niépce who, after years of research, produced the first photographic image in 1827. And although Niépce's merits were also recognized in 1839, it was Daguerre who was in the spotlight. A light that was so dazzling that Victore Fouque felt compelled in 1867 to title his book about Niépce's life and work "The Truth about the Invention of Photography" and to emphasize right away in the preface that an error, once it has taken root in the public mind, is accepted as truth.

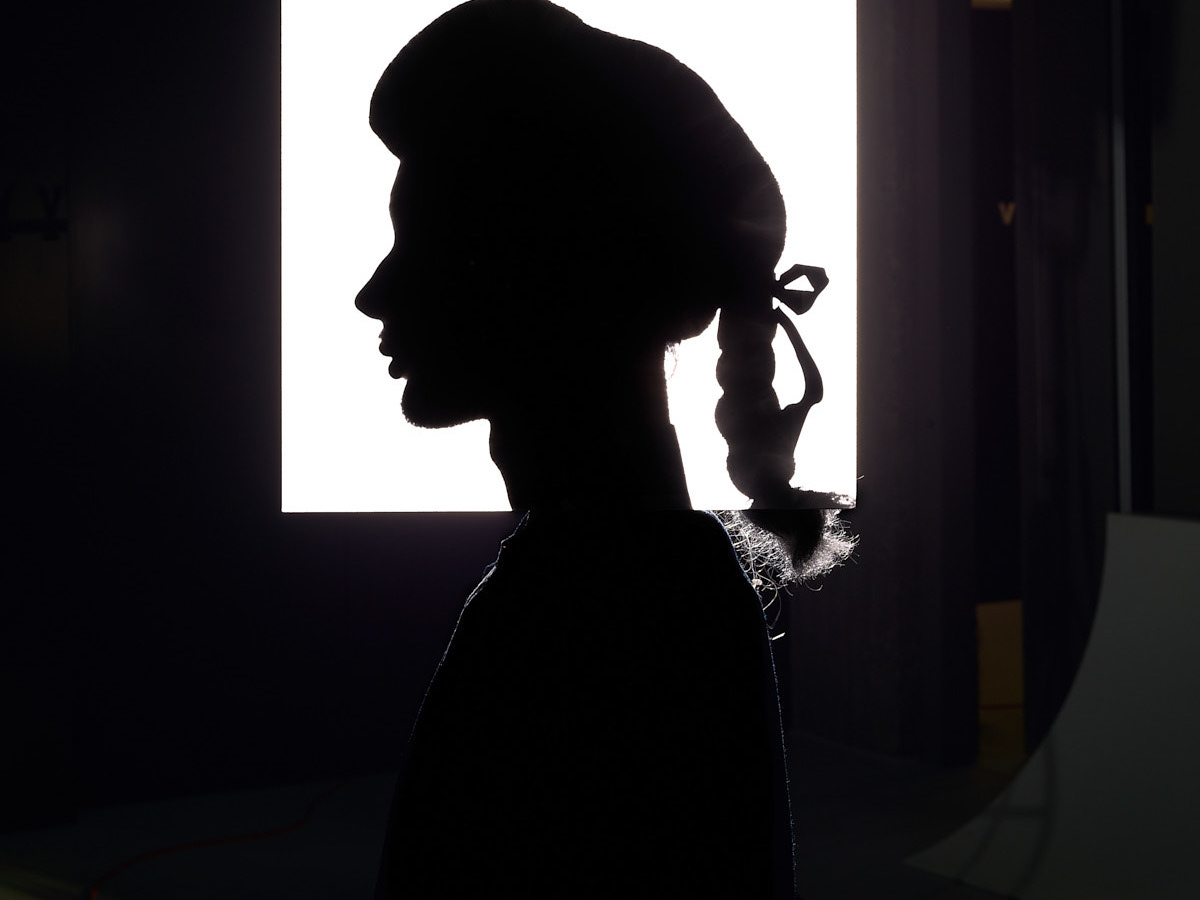

But Niépce has another fate to bear. There was no photograph showing him. His death took place in the pre-photographic period. There are photographs of Daguerre, as well as of Hippolyte Bayard and William Henry Fox Talbot, two other inventors of photography. But of Niépce - nothing! A drawing showing him as a young man, a bust made by his son Isidore after his death, and a portrait post mortem made by the painter Léonard François Berger in 1854.

We are proud to be able to counter this error of history with a photograph showing Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. For if we take as the basis of our conception of the physical appearance of the inventor of photography an oil painting done twenty years after his death, we may with equal justification take a photograph taken one hundred and eighty years after his death. And if the oil painting is an idealized form of representation involving the spirit, a photograph reflects all the more the spirit of Niépce - this inventor who in 1827 exposed a coated metal plate in a camera for eight hours and thus produced a completely blurred, coarsely structured image showing the view from his window and who was convinced that he would one day be able to do the world a great service with it.

We are proud to be able to counter this error of history with a photograph showing Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. For if we take as the basis of our conception of the physical appearance of the inventor of photography an oil painting done twenty years after his death, we may with equal justification take a photograph taken one hundred and eighty years after his death. And if the oil painting is an idealized form of representation involving the spirit, a photograph reflects all the more the spirit of Niépce - this inventor who in 1827 exposed a coated metal plate in a camera for eight hours and thus produced a completely blurred, coarsely structured image showing the view from his window and who was convinced that he would one day be able to do the world a great service with it.

On this day, there is neither a Rue Niépce nor a Parque Niépce in France.

portrait post mortem

C-print on aludibon, 80 x 110 cm, framed

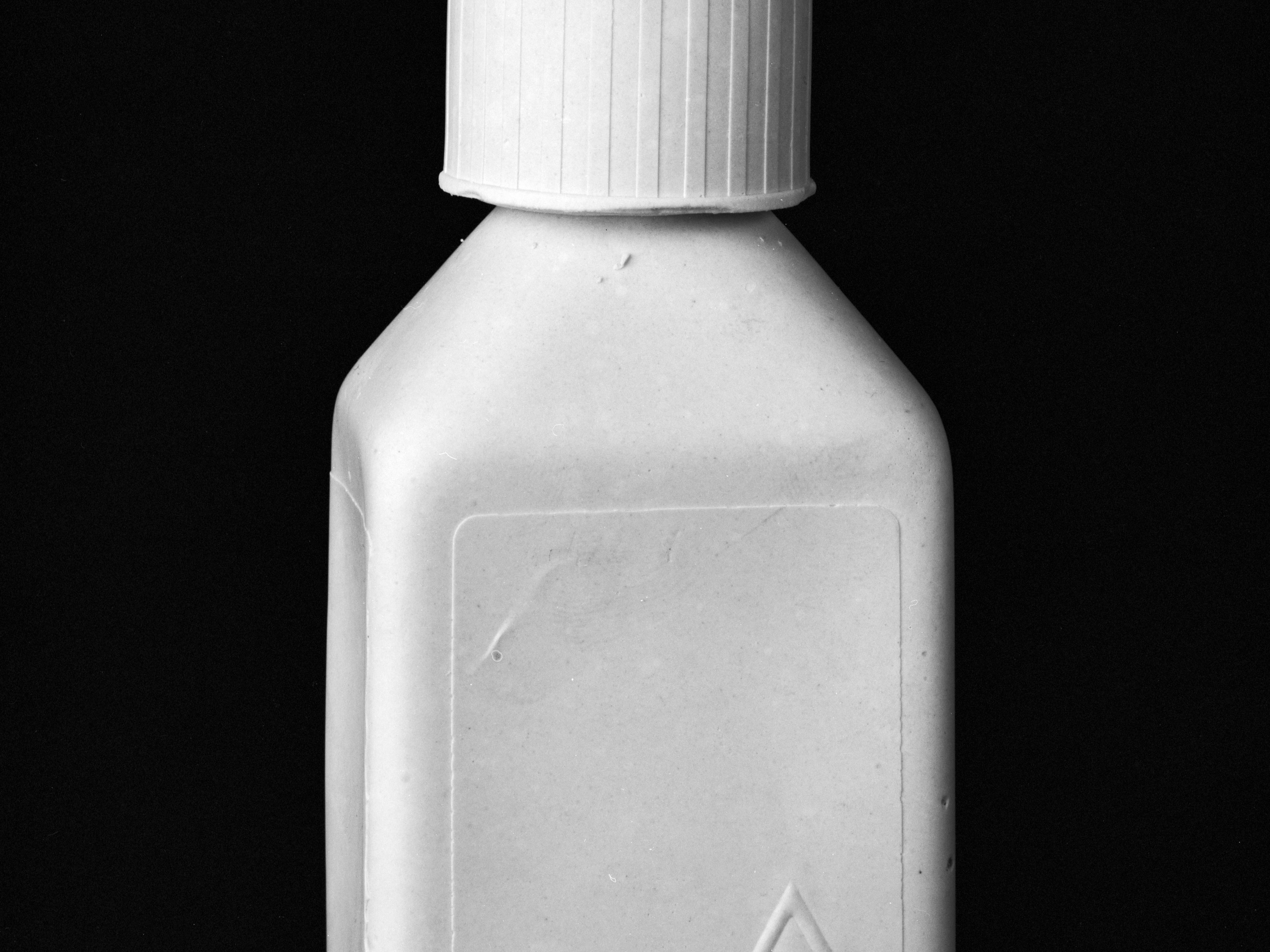

C-print on aludibon, 80 x 110 cm, framed